Christopher Collins Brings Extraordinary Background of Literary Pursuits

Christopher P. Collins’ childhood loathing for the German sausage known as Mettwurst helped lay the groundwork for his literary life.

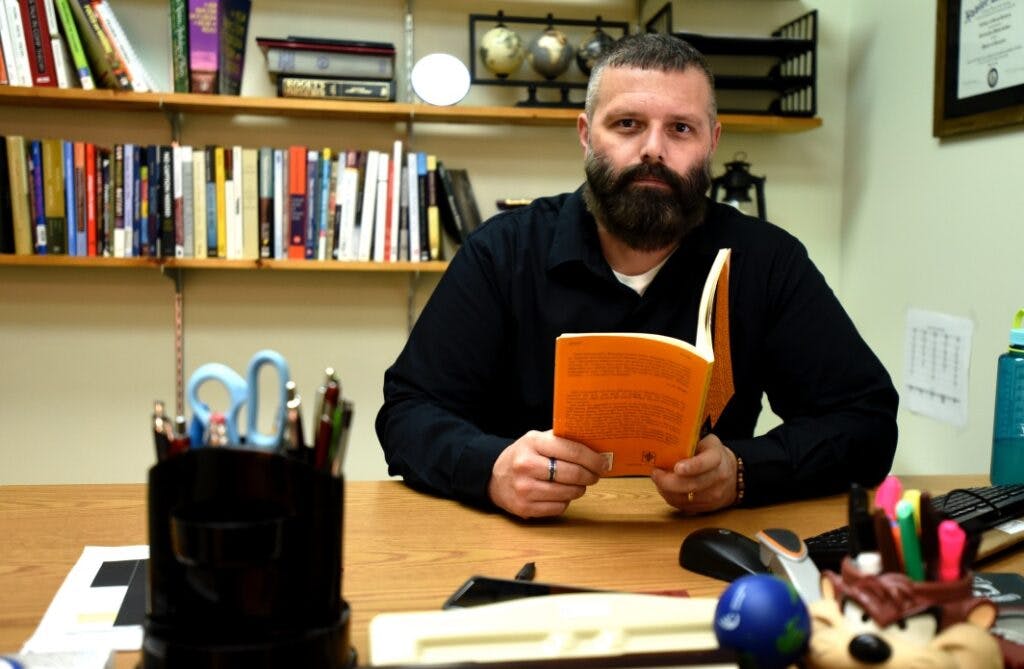

PICTURED: Chris Collins professes the importance of possessing skills in both creative and technical writing.

The award-winning poet, who is midway through his first year as an assistant professor of English at Wilmington College, recalled the day he refused to eat the spicy, pork hot dog for lunch as a fourth grader at his Catholic elementary school in rural Kentucky.

“I walked out of the cafeteria and went to the playground, where I led a meat revolution,” he said, adding that he successfully encouraged a legion of fellow students in chanting: “We paid for it. We don’t have to eat it!”

That stunt earned the rebellious Collins a detention and the “punishment” of having to memorize Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18, which begins with the famous line: “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” He can still recite the words from what is arguably the Bard of Avon’s most famous poem.

Collins soon incorporated controversy into his writing when, in fifth grade, he wrote a play about a married couple in which the husband was abusive. “The Sister called my parents because she thought I was being abused,” he said. “They convinced her, ‘He just has an active imagination.’“

His writing landed him in trouble again in the seventh grade when he wrote about a school bully being eaten by cannibals, a scenario that upset the bully’s younger sister and, in turn, annoyed the teacher. “I guess I’ve always been pushing the boundaries with my writing,” he added.

While Collins continued to enjoy creative writing, he never considered it for a vocation until he met the Franciscan priest, Father Murray Bodo, writer-in-residence when he attended Thomas More College in the mid-1990s. The professor’s reading from T.S. Eliot’s epic 1922 poem, The Waste Land, made a profound impression on the then-sociology/criminal justice major, who quickly switched to English and began devouring creative writing courses.

“Wow, it opened the floodgates for me,” Collins said, noting that Bodo remains a close friend and mentor some 20 years later. “I fell in love with poetry. If not for the priest introducing me to poetry, I don’t think I’d be here today.”

Collins, who won TMC’s Creative Writing Award as a senior, became enthralled with poetry. “I get lost in the experience of the speaker, the experience of feeling like you’re there,” he said, noting how poetry so succinctly captures that transformational experience of time and place, for him, better than any other form of creative writing.

“Poetry is a compact way to bring the reader into your person,” he said. “It’s beautiful to share a human experience with others: joy, sadness, love, pain, beauty.”

Many of those emotions are explored in Collins’ two acclaimed books in which he shares his direct experience with war through his poetry: Gathering Leaves for War: Poems (2013 and My American Night (2018).

Shortly after graduating from Thomas More, Collins joined the military and became a commissioned officer in the U.S. Army 120 days before the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist bombings. He served as a platoon leader in Afghanistan (2002-03) and completed two more combat tours as a detachment commander in Iraq in (2004-05 and 2009-10).

The description of My American Night notes how his war experiences “extracted their emotional shrapnel and examined their toll on his civilian life.” Collins’ poems “reveal the brutal ways” in which those vastly different aspects of himself as a citizen-soldier and as a husband and father often “collide and bleed into one another.”

In his poem, “Song for a Lost Team,” he writes: “Returning to my quarters after the chaplain’s service for the three soldiers killed, I laid a picture of my wife and our two kids on the green cot, then cut a small groove into my right thigh with the sharpened bayonet’s point — anything, just to feel.”

Collins said it was difficult to relive those experiences in his writing, yet in many ways it was liberating and cathartic.

“With all literature, I think you want to share the human experience with others,” he said, noting that when unveiling his poems for all to see, he’s actually “releasing” them from himself.

“When you take the chaos of life and put it into a poem, it’s like untwisting the cap off a soda jug that’s been shaken.”

Although no poet writes poetry to become rich and famous, Collins readily admits it’s gratifying to earn recognition for one’s work. Indeed, My American Night won the 2017 Georgia Poetry Prize and his poetry and prose have been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and the Paumanok Poetry Award, among others.

Collins is senior editorial assistant with The Cincinnati Review and he held a fellowship with Creative Nonfiction. His essays and poetry have been published or are forthcoming in Creative Nonfiction, Cutbank Literary Journal, Five Points, Pilgrimage and The Heartland Review.

That’s a lot of water under the bridge since his first published poem, when, as a second grader, his verse about a cat and mouse was printed in his church’s bulletin.

Collins, who lives with his wife and two children in Independence, KY, complemented his bachelor’s degree with a Master of Education degree at Xavier University, Master of Fine Arts in poetry from Murray State University and his Ph.D. in creative writing from the University of Cincinnati. He taught high school English for 10 years before coming to Wilmington College this fall, where he is a key faculty member teaching composition and creative writing, and helping usher in WC’s new professional writing minor.

“When I got my Ph.D., I wanted to be at a small, liberal arts college,” he said, noting that simply the sight of the Wilmington College grounds with all its green space made him “fall in love” with the campus.

“I enjoy being around students at such a small campus, where there’s such a sense of community and opportunity for one-on-one interaction,” he added. “I wanted a place where I could feel I belong as a member of the community — not just some teacher in some building.”

In spite of his success as a creative writer, Collins sees himself as a teacher-writer more than a writer-teacher. “To write is to want to share, not to build your ego,” he said. “I like to share with students. That’s why I teach writing.

“If I never wrote another book, I’d be OK with that as long as I could teach,” he said. “The writer-teachers are more concerned with their own work. I’m focused on students.”

Collins reflects on his first semester his at WC feeling pleased with how so many of his students progressed so well in their writing over three months. He looks ahead to the spring semester when he advises Woodhouse, the College’s literary magazine, and teaches a new course, Topics in Professional Writing.

“Professional (business and technical) and creative writing are different avenues in which to communicate, but it’s good for students to learn both,” he said. Indeed, there is a time and place for writing “three apples” versus “a trio of red skin tree nuggets.”

Collins said that, especially in this age of communicating in virtual reality via such nontraditional vehicles as social media and email, it is especially important to “clearly and concisely get your point across” in a professional manner.

“Writing is very important in making graduates more marketable.”