Research Is Part of Data Collection throughout North America

An estimated one billion birds die annually in North America after colliding with windows in the exterior walls of buildings.

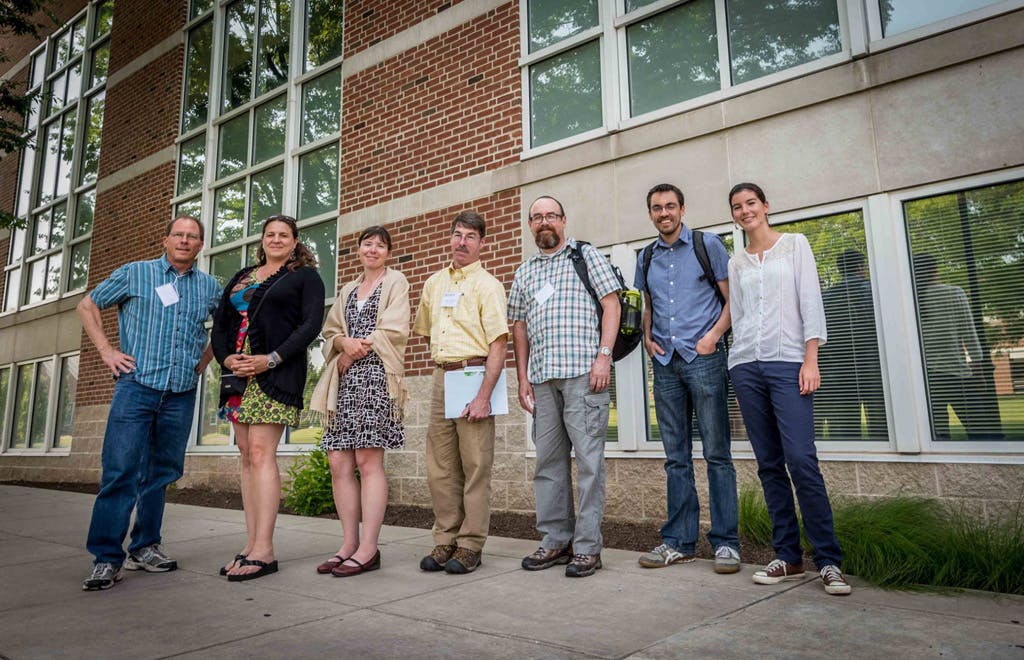

Pictured in front of a campus building with numerous windows at Elizabethtown College in 2015 are WC's Kendra Cipollini (second from the left) and a number of her bird-window collision research colleagues. They include, from the left, Stephen Hager, Augustana College; Kendra Cipollini, Wilmington College; Michelle Anderson, The University of Montana Western; Peter Saenger, Muhlenberg College; Thomas Contreras, Washington and Jefferson College; Bradley Cosentino at Hobart and William Smith Colleges; and Natalia Ocampo-Peñuela, Duke University.

Wilmington College’s Dr. Kendra Cipollini, associate professor of biology, was among an international team of more than 60 researchers who studied how the combination of local-scale building features, land cover and large-scale urbanization affects continent-wide differences in bird-window collision mortality.

The National Science Foundation funded the initiative in which the professor has participated for the past four years.

As a hands-on learning opportunity, Cipollini enlisted several of her students to assist with collecting data on birds colliding with campus buildings as part of their independent study projects in fall 2014. They included WC alumni Brad Kline, Ellen Short, Erin Short and Joe Stotte. Indeed, Cipollini has published numerous papers with student collaborators and continues to provide these types of hands-on, real-world, research opportunities for biology and environmental science students.

The results were recently published in a highly regarded professional journal, Biological Conservation, in an article entitled “Continent-wide Analysis of How Urbanization Affects Bird-Window Collision Mortality in North America.”

According to the report, the researchers monitored nearly 300 buildings that differed in size and local land cover types for bird-window collision mortality at 40 college and university campuses in North America. Researchers documented, during fall 2014, an average of more than eight bird carcasses discovered at each building site with one or more sites revealing as many as 34 carcasses during the several-month study period.

It indicated that the collision risk is primarily related to the amount of windows in buildings and environmental features immediately surrounding buildings.

Bird mortality is highest at large buildings (such as one-to-three-story low-rise office buildings) with many windows and lowest at small residential structures (such as single story houses) with relatively few windows. Moreover, bird-window collisions are more frequent at buildings surrounded by high levels of woody and herbaceous vegetation and few paved surfaces, such as parking lots and sidewalks.

Numerous bird species are affected by bird-building collisions, including species important in conservation that are declining through their ranges.

In addition to this research, Cipollini also published a paper, titled “A Review of Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata, Brassicaeae) as an Allelopathic Plant,” which she co-authored with Don Cipollini at Wright State University.

Their piece was part of a special issue of The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society on invasive species. It summarizes over a decade of research and includes a summary of published research by Wilmington College alumni Megan (Greenawalt) Bohrer, Wesley Flint, Sophie Hurley, Georgette McClean, Crystal (Wagner) Miller and Kyle Titus.

Within a week of its release, it became the Journal’s most downloaded paper in the past 12 months and it continues to garner attention in the scientific community.